After a long and happy lifetime of never reading any Henry James ever except for "

Daisy Miller" in a sophomore year English class, I finally tackled

The Bostonians.

|

| The Bostonians |

In the past, James had always struck me as unbearably stuffy: his sentences had more clauses than a mall at Christmastime (ha!), and his paragraphs went on for pages and pages, and everyone was always making themselves so unbearably happy because of their tight, tight Victorian corsets. Basically, he seemed like a chore. But I had started

The Bostonians in grad school, and I hate leaving a book half done, especially when I was enjoying it in the first place.

The Bostonians, despite being one of James's lesser-known novels, does not disappoint. I suspect that it's rarely read these days because it's so topical: it deals primarily with women's suffrage, or, as it was known in 1885, "

The Woman Question." The novel centers around Verena Tarrant, a beautiful, red-headed young woman who just happens to be an electrifying public speaker interested in equal rights for women. Her family is poor, and her father is a disreputable

mesmeric healer, which means that Verena is not only talented and on the rise in society, she is also dismally unprotected and without means of her own.

|

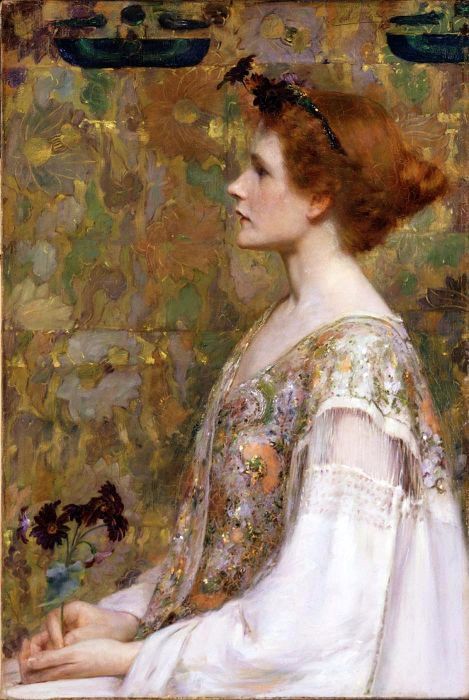

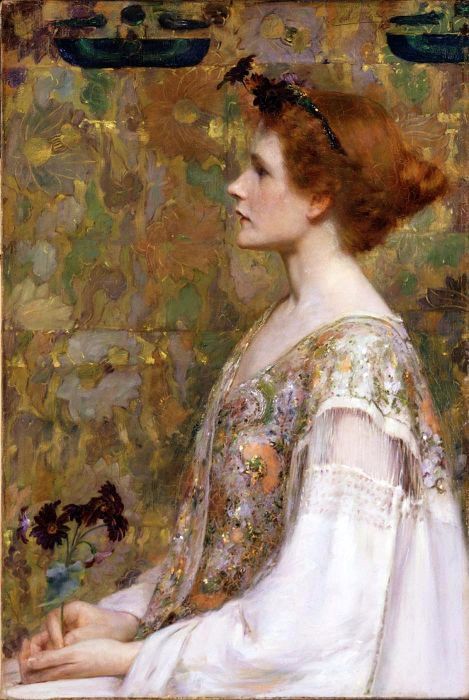

| Woman with Red Hair, Albert Herter, 1894. |

At her first speaking engagement in Boston, Verena meets Olive Chancellor and Basil Ransom (do I even need to mention those uber-obvious thematic names? oy!), two cousins who both begin, in their own ways, to woo Verena.

Olive wants Verena to stay unmarried, to live in Olive's home, and to travel the world, bringing a message of equality to the world. Basil Ransom, on the other hand, wants Verena to marry him and leave the public eye for good so she can spend the rest of her life entertaining and tending him (I'm not kidding--he actually says this). As the book builds toward its agonizing climax, Verena is forced to choose between a life on the world stage and a life that can be contained in a single sitting room.

What fascinated me about this book isn't its subject or even its plot, it's the fact that it's a novel without heroes. Verena is lovely and innocent and very sweet, but she also bends happily to the will of whomever's in the room at the time. She's a pushover by nature and by station. Olive Chancellor is zealous, brittle, tyrannical, and manipulative. Ironically, for all her passion for women's rights, she allows Verena no freedom of her own. Basil Ransom is handsome and charming but skin-crawlingly insidious: his love for Verena is a passion for possession and control. He wants to marry her, but primarily as a means of keeping her from "parroting" feminist beliefs that he doesn't believe she could possibly understand.

Verena is only given two extreme choices in the novel and no chance of winning, and that, I think, is the entire point. James refuses to espouse either ideology in this novel: he seems disgusted with the rhetoric of the women's rights movement (which he portrays as extremist and heartless), and yet he portrays their detractors (traditionalist Victorian males like Ransom) as pirates and captors.

|

| Boston, 1880s. |

Once she emerges into the upper classes of

Victorian America, Verena cannot escape. In a world where she was truly free to build her own life, Verena Tarrant wouldn't have had to pledge herself to the rich yet spartan Olive Chancellor as her patron, ruler, and near lover, nor would she have to succumb to the seduction of the romantic but appallingly misogynistic Basil Ransom. If she were free, she wouldn't have to choose between being a feminist zealot or an obedient wife, a Northerner or a Southerner, a thinker or a feeler. She could be a little bit of all of these things and, most importantly, her own self.

But Verena is not free, which makes James's novel incredibly suspenseful and sad. If you're going to give James a try, I strongly recommend

The Bostonians.