|

| The Bostonians |

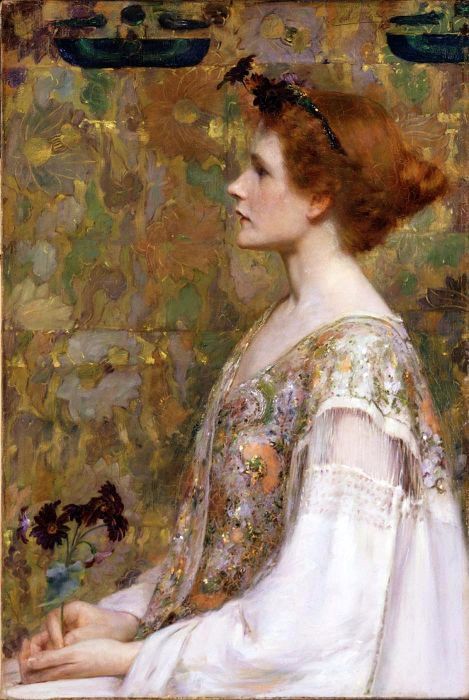

The Bostonians, despite being one of James's lesser-known novels, does not disappoint. I suspect that it's rarely read these days because it's so topical: it deals primarily with women's suffrage, or, as it was known in 1885, "The Woman Question." The novel centers around Verena Tarrant, a beautiful, red-headed young woman who just happens to be an electrifying public speaker interested in equal rights for women. Her family is poor, and her father is a disreputable mesmeric healer, which means that Verena is not only talented and on the rise in society, she is also dismally unprotected and without means of her own.

|

| Woman with Red Hair, Albert Herter, 1894. |

Olive wants Verena to stay unmarried, to live in Olive's home, and to travel the world, bringing a message of equality to the world. Basil Ransom, on the other hand, wants Verena to marry him and leave the public eye for good so she can spend the rest of her life entertaining and tending him (I'm not kidding--he actually says this). As the book builds toward its agonizing climax, Verena is forced to choose between a life on the world stage and a life that can be contained in a single sitting room.

What fascinated me about this book isn't its subject or even its plot, it's the fact that it's a novel without heroes. Verena is lovely and innocent and very sweet, but she also bends happily to the will of whomever's in the room at the time. She's a pushover by nature and by station. Olive Chancellor is zealous, brittle, tyrannical, and manipulative. Ironically, for all her passion for women's rights, she allows Verena no freedom of her own. Basil Ransom is handsome and charming but skin-crawlingly insidious: his love for Verena is a passion for possession and control. He wants to marry her, but primarily as a means of keeping her from "parroting" feminist beliefs that he doesn't believe she could possibly understand.

Verena is only given two extreme choices in the novel and no chance of winning, and that, I think, is the entire point. James refuses to espouse either ideology in this novel: he seems disgusted with the rhetoric of the women's rights movement (which he portrays as extremist and heartless), and yet he portrays their detractors (traditionalist Victorian males like Ransom) as pirates and captors.

|

| Boston, 1880s. |

But Verena is not free, which makes James's novel incredibly suspenseful and sad. If you're going to give James a try, I strongly recommend The Bostonians.

No comments:

Post a Comment